|

|

|

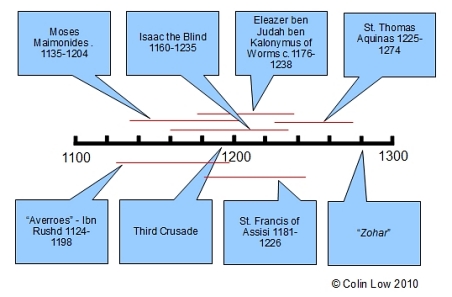

Early Kabbalah It is difficult to understand why Kabbalah exists without understanding the world of the 12th century of the Common Era in which it came into being. The northern Mediterranean from the Pyrenees to Byzantium was Christian. The southern Mediterranean from Spain to Syria (with the exception of the short-lived Crusader kingdom of Outremer in Palestine and Syria) was Muslim. The economic realities of the Roman Empire remained intact: cities require resources, and resources require transport. The major cities were still scattered around the edge of the Mediterranean, or on large river systems such as the Rhone, the Loire, the Seine, the Rhineland, and the Danube. Trade and communications were just as important as they had been in Roman times, and the trading connections of Jewish communities spanned the known world. There were Jewish communities in every city on both sides of the Mediterranean. There were Jews in England financing the ambitions of the English throne. There were Jews in Persia. Jews had been living in India since Rome was still a village by the Tiber. There were Jews travelling the Silk Road to China. Most of the great cities of the world of Late Antiquity (with exceptions such as Rome, Marseilles and Byzantium) were in Muslim hands, and so was most of the learning of antiquity. The intellectual heritage of late Hellenism - mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, magic, chemistry had been available in Arabic translations for centuries. The Jewish community in Muslim Spain, an important conduit between the cultures to the north and south of the Mediterranean, was highly educated, highly regarded, and multi-lingual. The murderous Second Crusade (1147-49), which decimated Jewish communities along its path, had failed to restore Outremer to the Christians. Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (1125-1204 CE), physician to the great Saladin himself, wrote The Guide for the Perplexed, the most important and influential work of Jewish religious philosophy of all time. It was written in Egypt, and in Arabic, but quickly became an item of ferocious and partisan debate in every Jewish community. This was a world dominated by religion. Three trends stand out. The first was friction between Christianity and Islam, with long-running territorial conflicts in Spain and in the Holy Land. The second trend was the assimilation of Greek philosophy into religion. This happened more-or-less concurrently to Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, with much of the impetus coming from great Islamic thinkers such as Avicenna, Alkindi and Averroes. A third trend was a passionate commitment to religion at the expense of comfort and possessions. This ascetic tendency affected Jews as much as Christians, so that we find the pious and devout Chassidim in the Rhineland at the same time as St. Francis of Assisi in Italy. It is in this passionately religious world of monasteries, ascetics, miracles, wandering friars, pilgrimages, crusades and ferocious debate that we find a resurgence of European Jewish mysticism, and it came from several directions. In the Rhineland, the famous Kalonymus family, who were reputed to have migrated there from to toe of Italy in the time of Charlemagne, had preserved ancient magical and mystical lore originating from Palestine and Babylonia. The family preserved traditions of the legendary Aaron ben Samuel ha-Nasi of Bahgdad, who was reputed to have brought kabbalah (by which is meant secret esoteric knowledge) to Europe. Central to this group, the Chassedei Ashkenaz, were R. Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg, often called 'the pious', and his disciple R. Eleazar of Worms. Although deeply immersed in the mysteries of the kavod (Divine Glory) and a source for a great deal of language mysticism and gematria, the Chassedei Ashkenaz are regarded as a source for many of the ancient traditions that influenced Kabbalah, rather than a stage in the development of Kabbalah itself. From the Muslim world, and Spain in particular, came works influenced by Hellenistic religious philosophy, in particular the Chovot ha Levavot (Duties of the Heart) of Bahya ibn Paquda. This was an important ethical work because it reframed Jewish religion from an exterior social context ("the duties of the body") to an interior personal context ("the duties of the heart"), and marked an important transition in the path towards a personal mysticism. It was influenced by the mysterious Bethren of Purity, a group from Basra in Iraq who produced the encyclodaedic Rasa'il ikhwan as-safa' wa khillan al-wafa. One should also mention the Fons Vitae of Solomon ibn Gabirol (c. 1021-1058), who sought to reconcile Neoplatonism with Jewish religion, and exerted much influence on medieval Christian scholastics. As general cultural background one should also mention important works of Neoplatonic Christian theosophy such as the De Divisione Naturae of Johannes Scotus Eriugena. The publication in Southern France of a strange and enigmatic text known as the Bahir was the event that most commentators, ancient and modern, regarded as the true beginning of Kabbalah. Attempts to establish its authorship or provenance have been largely unsuccessful, although some parts appear to be based on a much older document, the Raza Rabba. The Bahir has a marked gnostic character, but the reasons and sources for this remain obscure, despite much analysis and speculation. The first group of individuals that can be specifically identified with Kabbalah is the group surrounding R. Isaac the Blind (c. 1160-1235) in Provence: his father, the famous Talmudic commentator R. Abraham ben David of Posquieres (c. 1125-1198); his grandfather R. Abraham ben Isaac of Narbonne (c. 1110-1179); his student Azriel ben Menahem of Gerona (1160-1238), and the mysterious figure of Jacob ben Saul of Lunel (aka Jacob the Nazirite). At the risk of over-simplification, the emergence of Kabbalah can be seen as a result of reinterpreting the traditional literature of Judaism in the light of certain ancient texts, such as the Sepher Yetzirah, the Shi'ur Komah, and the Merkavah and Hekhalot texts, in a cultural and intellectual enviroment pervaded by ideas derived from Hellenistic philosophy. There is also a generic kind of gnosticism latent in traditional sources that was developed into powerful mythological images that gained strength throughout the centuries. The main focus for Kabbalah then moved to Northern Spain, where its main conceptions attained a stable form, culminating in the publication of the most important and influential of Kabbalistic texts, the Zohar. Important kabbalists from this period are Azriel of Gerona (1160-1238), R. Moses ben Nachman ("Nachmanides") (c. 1194-1270), R. Jacob ben Sheshet of Gerona , and the Kohen brothers Jacob and Isaac. The culmination of the early phase was the publication of a number of classic works by R. Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla (c. 1248-1305), R. Abraham Abulafia (c. 1240-1291), and the author or compiler of the Zohar, R. Moses of Leon (c. 1250-1305). It is worth noting that within the timeframe of the origins of Kabbalah in Southern France, the Dominican Order came into being in the same region. Although the initial impulse was the exterpation of the Albigensian heresy, the Order was to play a major role in persecuting Jews for many hundreds of years, and was instrumental in one of the greatest catastrophes in Jewish life prior to the Holocaust. See also:The Early Kabbalah, Joseph Dan, Ronald C. KienerThe Origins of the Kabbalah, Gershom Scholem Jewish Mysticism: The Middle Ages, Joseph Dan Return to Historical Background |